User Experience Designer Harry Brignull recently opened submissions for an event called the Dark Patterns Awards, with the goal of shining the spotlight of shame on companies and organizations that resort to shady techniques in doing business with customers. The steps are simple enough: take screenshots and photos of the offending product, email them in, and all will undergo a voting process and an awards ceremony on the Dark Patterns website.

What is a Dark Pattern?

But let’s go back and examine this phenomenon a bit more closely. Dark Patterns aren’t mere background images that tile, but the opposite of what designers call a “pattern”. The term “pattern” is used in interface design to denote a familiar, widely-used technique in presenting information and handling interactions in a certain way.

Yahoo!, for example, has its own Design Pattern Library you can browse for reference, where you’ll see interfaces like photo galleries, tag clouds, navigations, and so on. Other pattern sites include UI Patterns, Interaction Design Patterns on Welie.com, and Mobile UI Patterns.

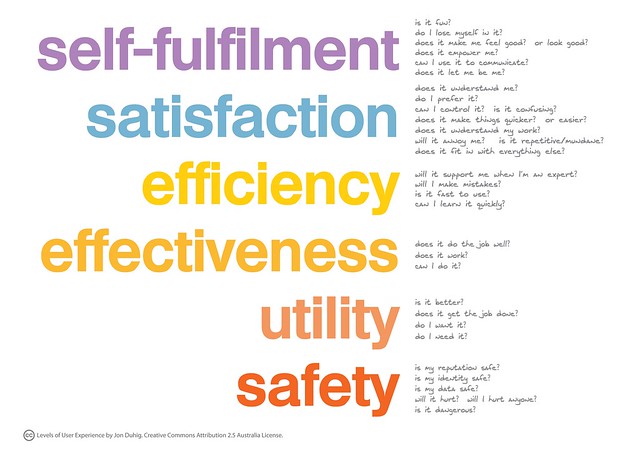

Patterns are created to address a particular situation and address goals and obstacles a user may encounter in that instance. Patterns are models other designers can follow so they don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Following a certain pattern also benefits users because it keeps the environment they’re interacting with at a comfortable level. It lets them avoid having to learn the interface from scratch and saves both parties time and effort, leading to more successful, satisfying transactions.

Now “dark patterns” are what you might expect to be the opposite of that. Instead of using psychology to make user experience better, “dark patterns” exist to confuse customers to make decisions they wouldn’t make outright. This is often done to make more money from a transaction, or perhaps to extract more sensitive information from them. The worst trait of a dark pattern is that it’s intentional in its sneaky and malicious nature.

However, it’s also possible for you to be doing this in your own ventures unknowingly, perhaps because someone else thought it was a legit idea, or you were using a plugin or service that did. Well now there’s no reason to be ignorant.

Avoid these Dark Patterns!

The slideshow embedded above goes through some of the most popular examples of dark patterns that exist on not just real websites, but well-known and trusted ones at that. Even products targeted at children!

Extra purchases: If you sell products on your website, do you automatically sneak in extra products to a customer’s shopping cart under the guise of an “added value” except they don’t actually come free?

Vague or misleading copy: Does the start of your landing pages and campaigns say one thing in the first paragraph, but actually withhold information that is revealed only in the next paragraphs or fineprint? Here’s an example, as mentioned in this A List Apart article:

Don’t worry your card will NOT be charged for membership during its 30 day trial and there is no obligation to continue with the service after the trial period.

If you choose to stay as a member after your free 30 day trial period your card will be charged a monthly membership fee of £14.99.

The first paragraph gives you the idea that you will not be locked in to the service after 30 days. However, the second paragraph implies that signing up will, by default, charge your credit card monthly unless you remember to opt out after that 30-day trial period.

Convoluted settings: Do you make it a challenge for your customers to find the preferences they need and bank on their confusion and frustration to just leave the default ones on?

The likes of Ryan Air and GoDaddy have very intimidating checkout pages that it may just lead users to make purchases they didn’t want in the first place. These days, the poster child for this dark pattern has to be Facebook and its privacy settings.

Here’s a great TED Talk by Dan Ariely on the same topic, containing both user interface examples and real-world examples: Are we in control of our own decisions?

It’s a great question on its own. But are you contributing to that confusion as well?